Why are graphics important to successful trial lawyers?

Pictures amplify and clarify by selective inclusion, order of presentation, use of emphasis, and by use of favorable or negative depictions — all these things work together to present an organized, coherent experience for your audience.

Our team specializes in developing graphics that capture complex issues and present them in a simple, clear way. Contact us to learn more about how we can help.

Years ago, a lawyer I knew asked me to produce some illustrations to help his expert witness explain a case of brain injury to a jury. I drew perspective views juxtaposed with CT scans to show a void in the cerebral cortex left by the trauma. My client won a trial verdict, and at the victory dinner, he cited the graphics as being key to the award. Even though these pictures were only seen by a few people, they helped produce a significant result. All this was a revelation to me — I had never even heard of “demonstrative evidence.” A few years later, I joined FTI to make it my life’s work.

To the proverbial hammer, everything looks like a nail. So, of course I think graphics are important... But, graphics are of critical importance to trial lawyers simply because they are critical to your audience: the judges, arbitrators, and jurors who will decide your case. They make decisions based on their understanding of the facts, and as we explore here, that understanding is shaped more by what they see than by what they read or hear.

The power of graphics

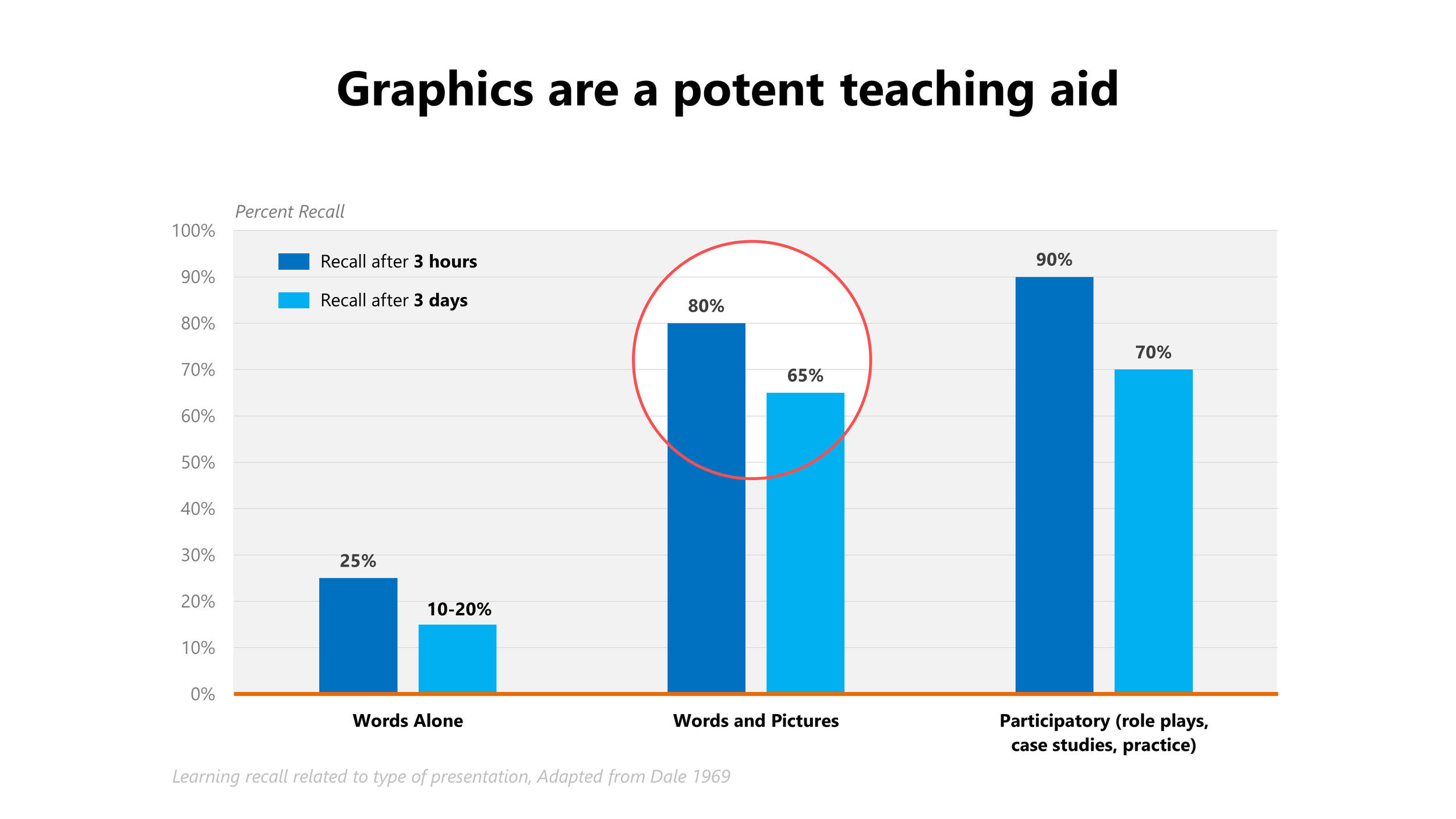

The power of pictures is not a little thing — it is a several hundred percent improvement in recall, short and long term, as shown by research published in the late 1960s by Dale, et al. Many studies, including by Houts, et al. in 2006, show a similar-scale improvement in comprehension using pictures as compared with words alone.

In the late 1960s, Dale, et al. showed 300%+ increases in short and long term retention with words and pictures over words alone.

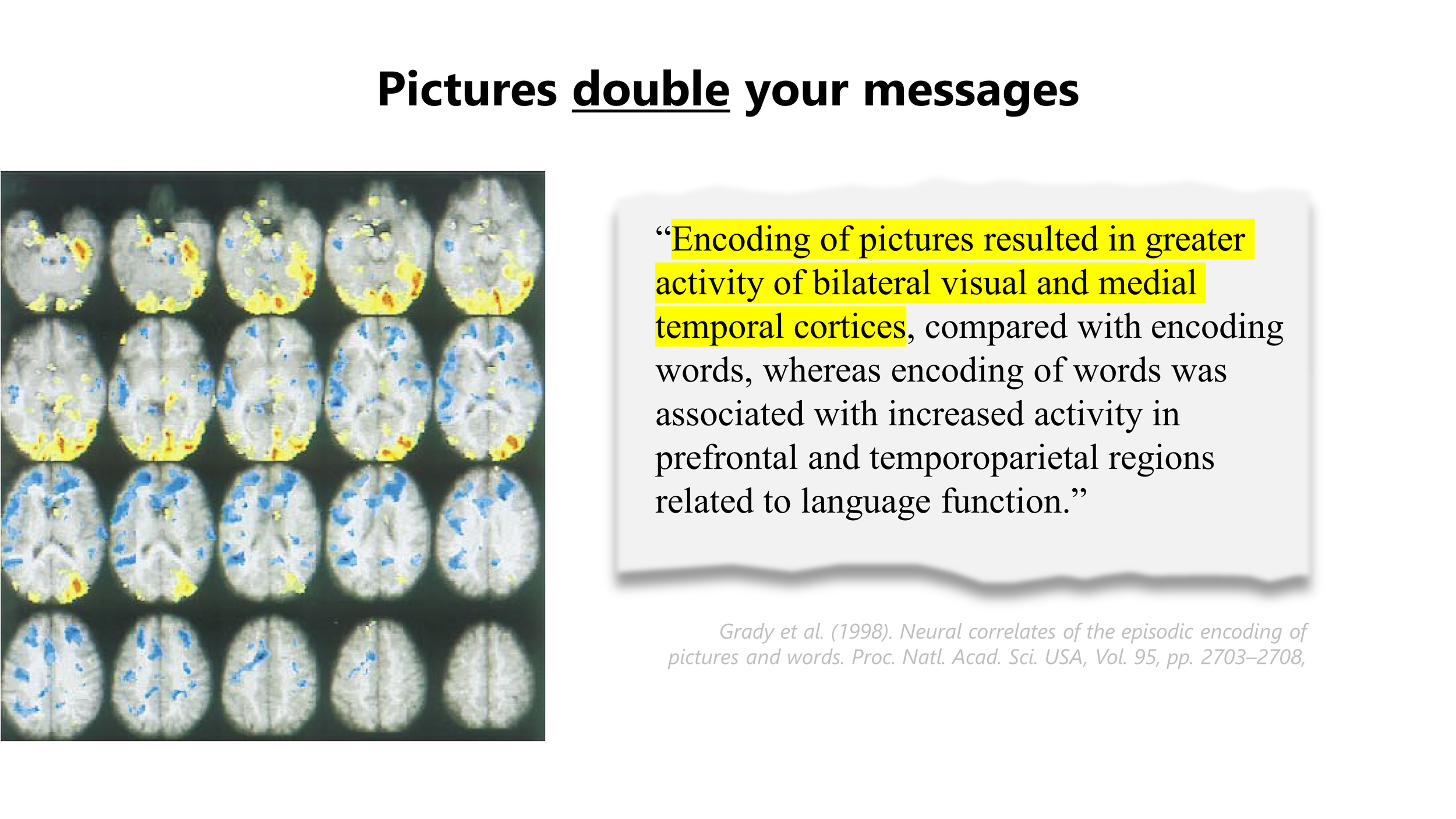

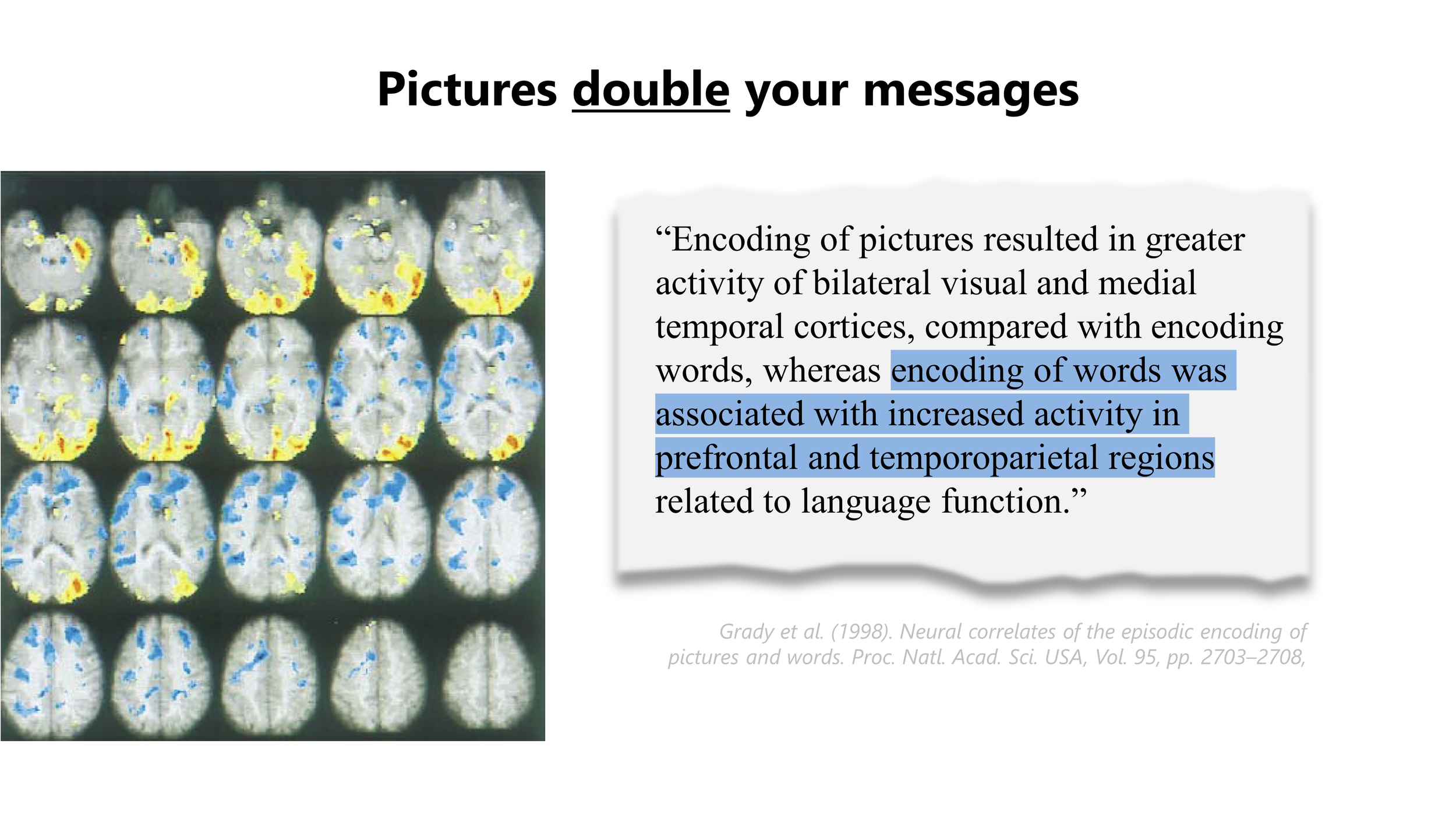

In the late 1990s, Grady et al. probed the neurophysiology of this phenomenon: “A striking characteristic of human memory is that pictures are remembered better than words. We examined the neural correlates of memory for pictures and words in the context of episodic memory encoding to determine material-specific differences in brain activity patterns. To do this, we used positron emission tomography to map the brain regions active during encoding of words and pictures of objects.”

They found that the subjects seeing pictures showed large distinct regions of brain activity, separate from and in addition to regions activated by verbal stimuli. That is, clinical proof of the years-old two-track (visual and verbal) theory of learning, and an answer to why pictures have power: they occupy more of your audience’s brains.

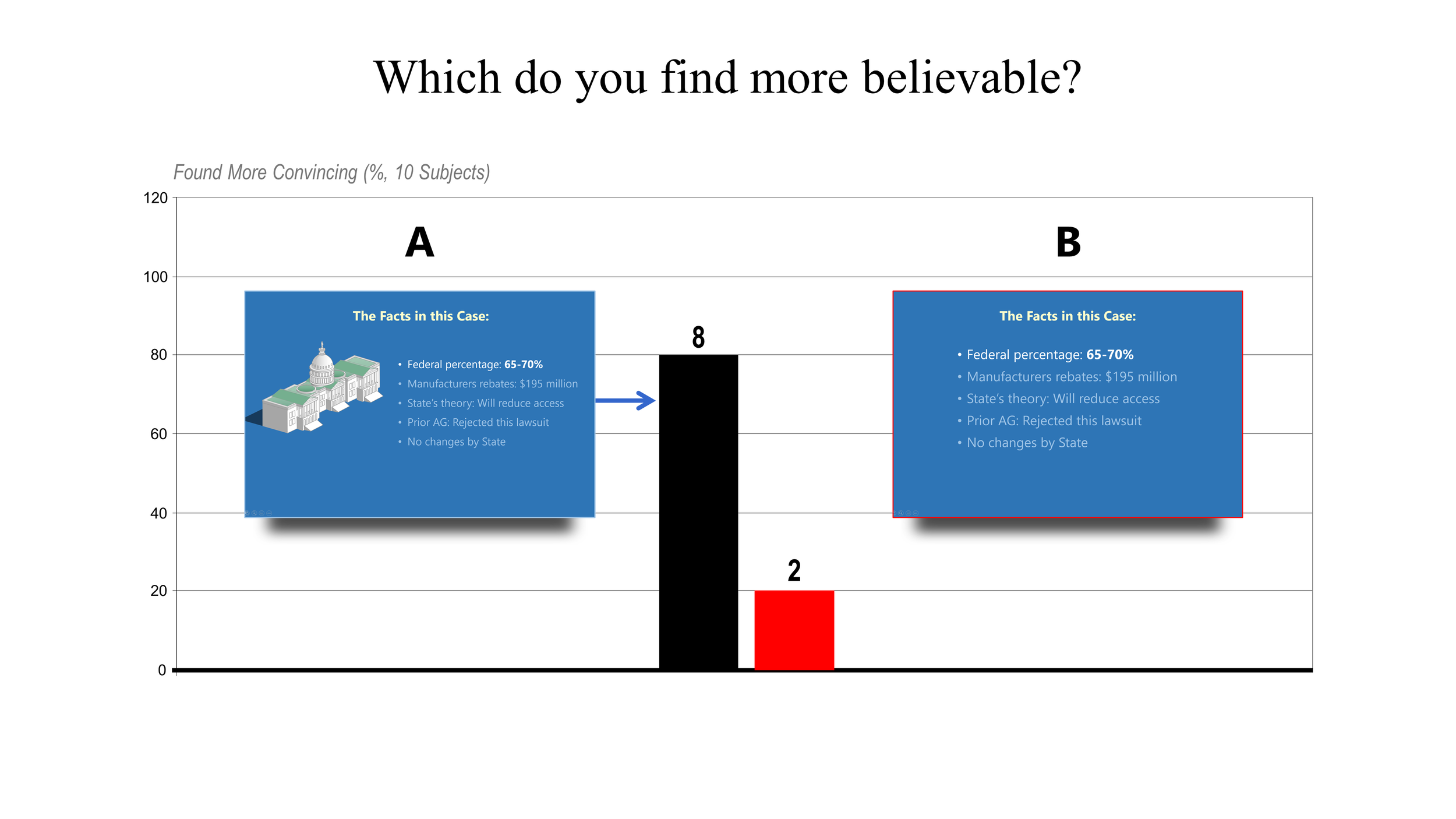

Graphics may have another effect that is of even more profound benefit to trial lawyers: in a small group study we did as an adjunct to a case focus group, we saw a multifold increase in the reported believability of images that include pictorial content over those with verbal content alone.

In the late 1990s, Grady et al used PET scanning to capture dramatic images that proved adding pictures to verbal narrative significantly increased the area of brain activity. In fact, viewing pictures involved additional, separate regions of the brain.

I don’t suggest that trial presentations should be festooned with meaningless pictures, far from it. Your graphics should work hard for you, explaining, proving, and helping to carry the cognitive load of case facts and evidence.

Shouldering the cognitive load

The adage may be “explaining is losing,” but in my experience the better motto is “be the teacher.” I’ve never heard of jurors saying “thanks for not explaining this,” but many times I’ve heard the opposite. Jurors hate to be confused, love to understand and love to feel smart. This presents a huge opportunity for the trial lawyer, and good graphics help to exploit it.

In multiple small group tests, we found that mock jurors consistently and overwhelmingly selected images that included pictures as more believable than those without. Even when challenged in individual interviews, jurors confirmed this strong bias.

Accordingly, the lack of a good visual explanation, in many cases, leads directly to judge or jury confusion and a negative outcome: an unfavorable settlement or bad trial verdict. In one particularly difficult case, the team struggled to gain an understanding — and good graphics to explain — the disputed cutting-edge technology. One defendant settled after a focus group showed that jurors just didn’t get it. The other defendant stayed in the game, working with us and the experts to develop a compact verbal and visual explanation of the technology at issue. They went to trial with a jury and won.

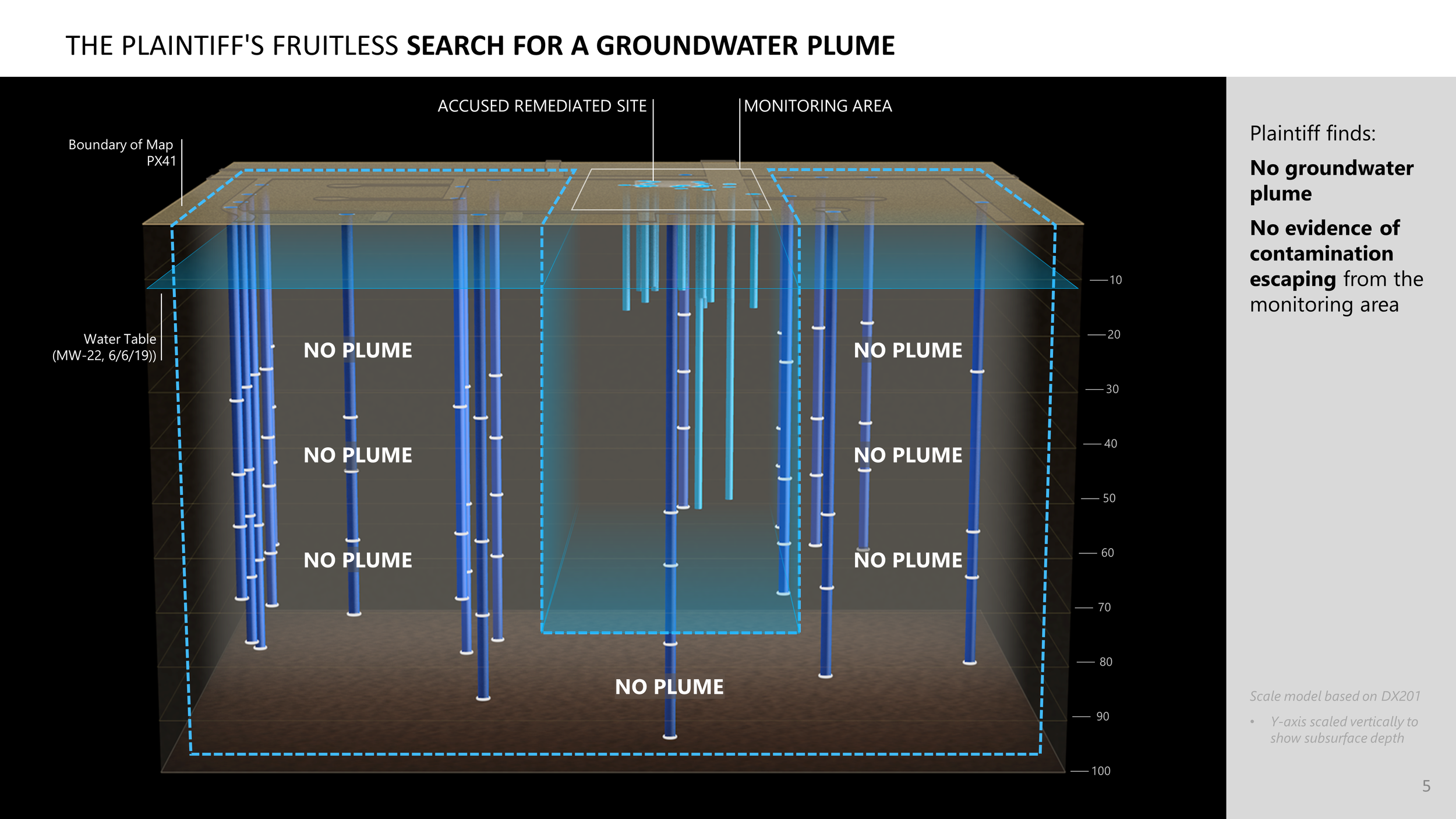

With this 3D animation, jurors receive an orientation to the basic hydrogeology of an accused site. At the same time, they build the visual and verbal vocabulary they need to understand and agree with the defense case.

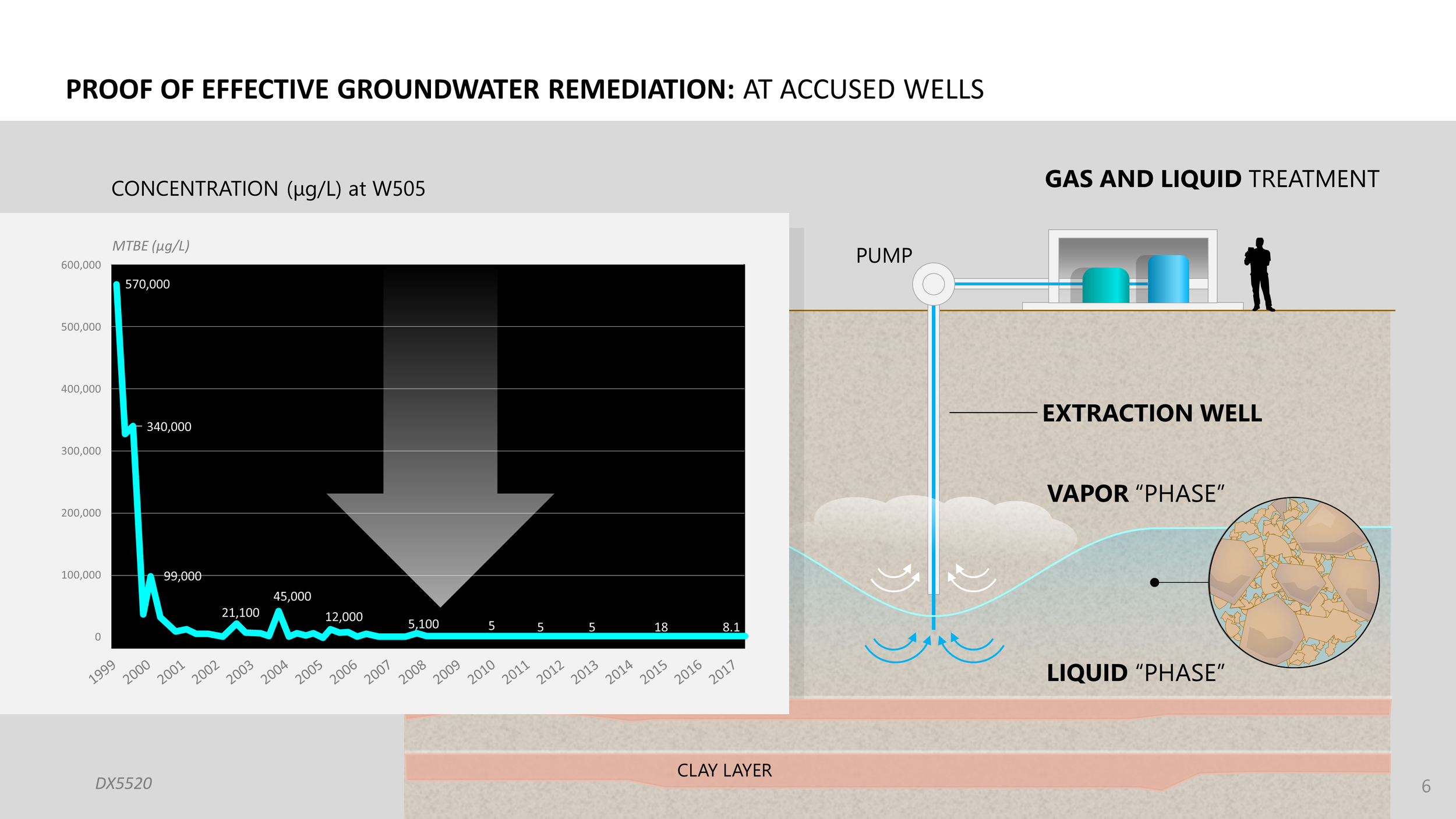

Similarly, and in the same case, this 2D animation explains how remediation works, and shows the proof we have that it is working at the accused site.

Einstein is believed to have said, “If you can’t explain it to a six-year-old, you don’t understand it yourself.” I don’t know if that’s accurate, but I know it’s true. Lawyer and artist need to attain (sometimes by dint of repeated effort) a robust understanding of the issues in order to translate them into a visual and verbal language a layperson can understand and act on. In other words, you and your graphic designer need to understand it deeply to be able to present it simply.

Embodying your case

Good graphics are not an accessory to your case, good graphics are your case. This pertains especially to jurors, for whom the big takeaways are what they see on screen or on the boards you put in front of them. Themes, chronologies, evidence and arguments can and should be woven into, and given substance by, your graphics.

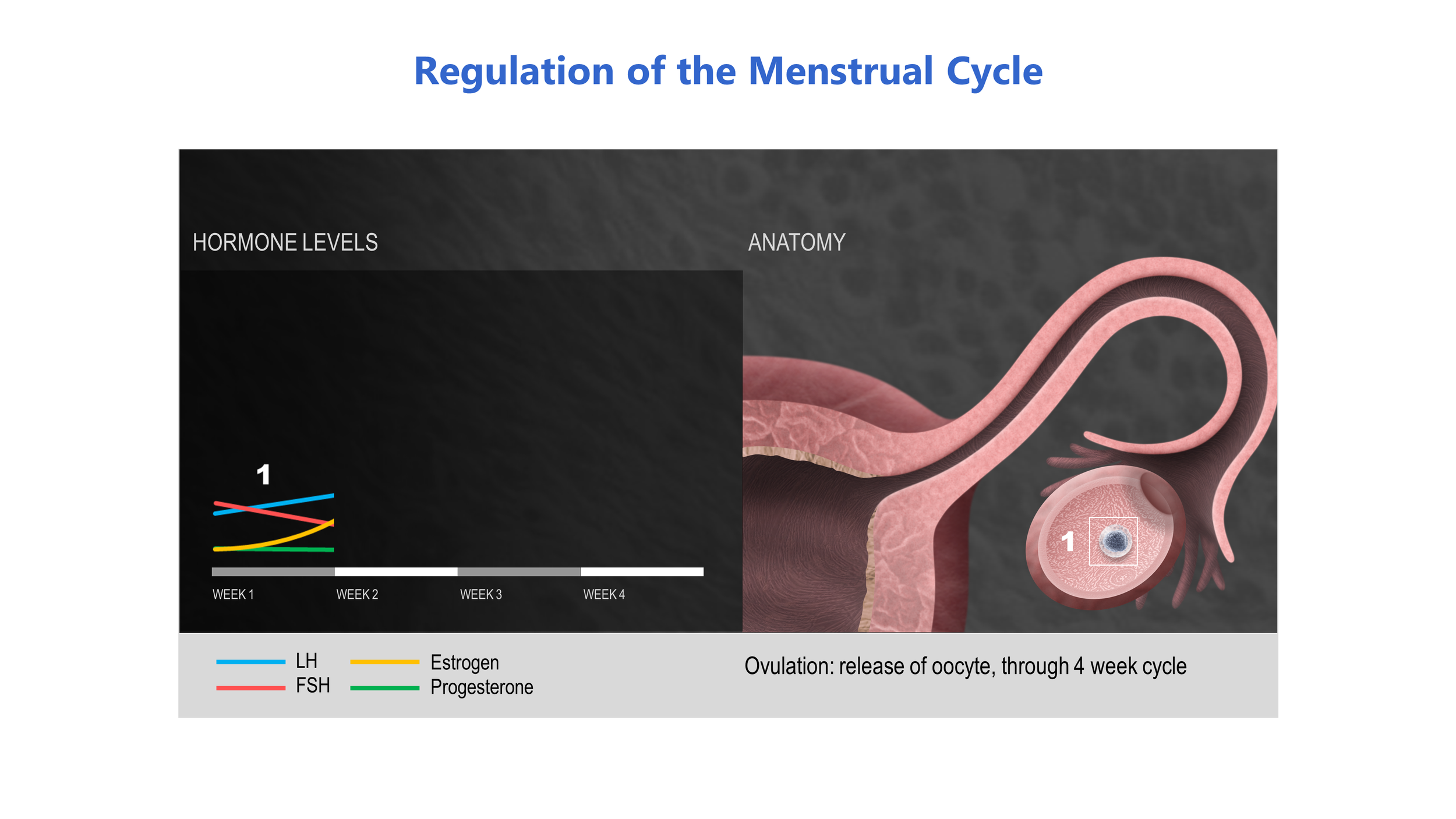

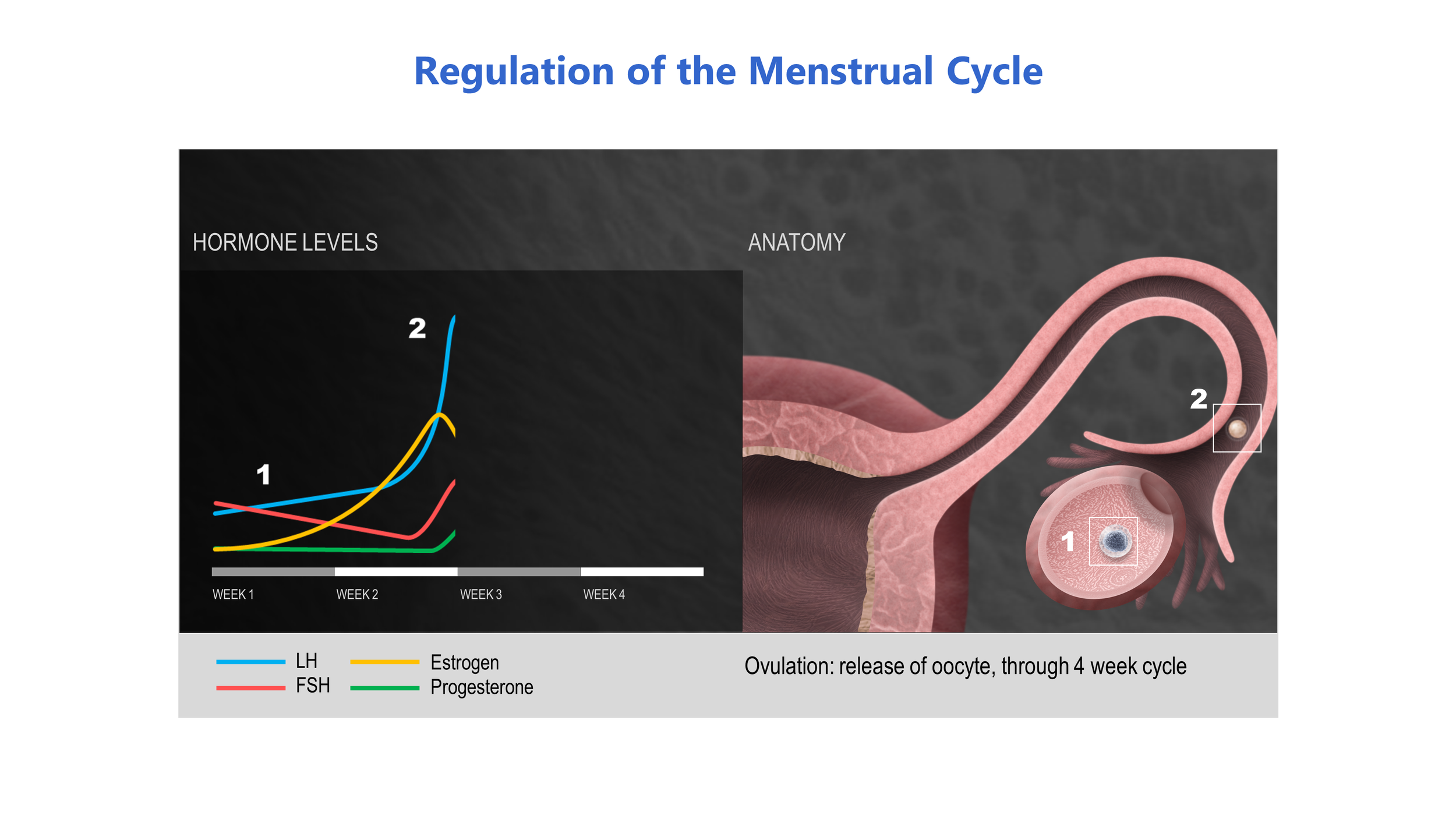

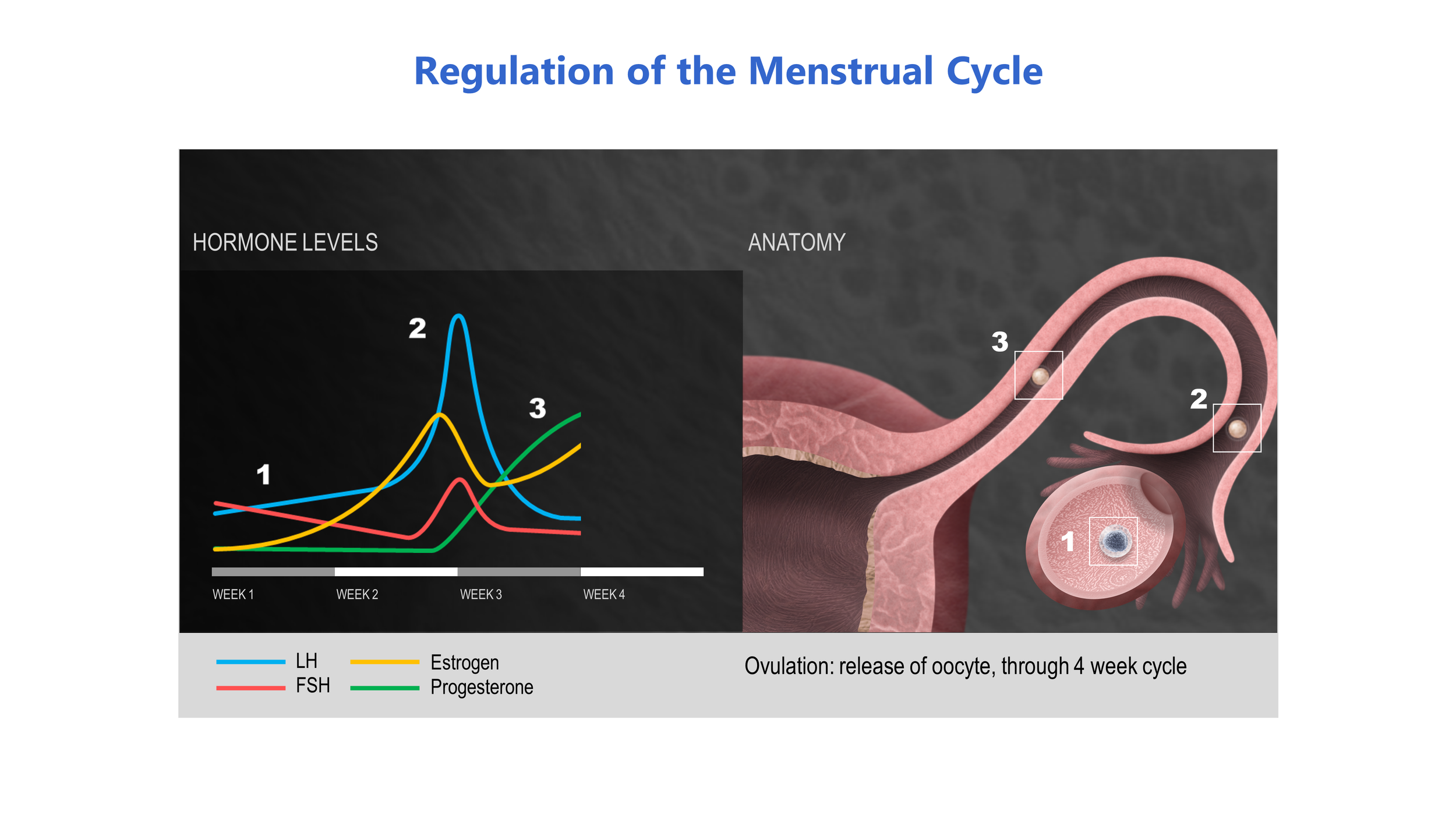

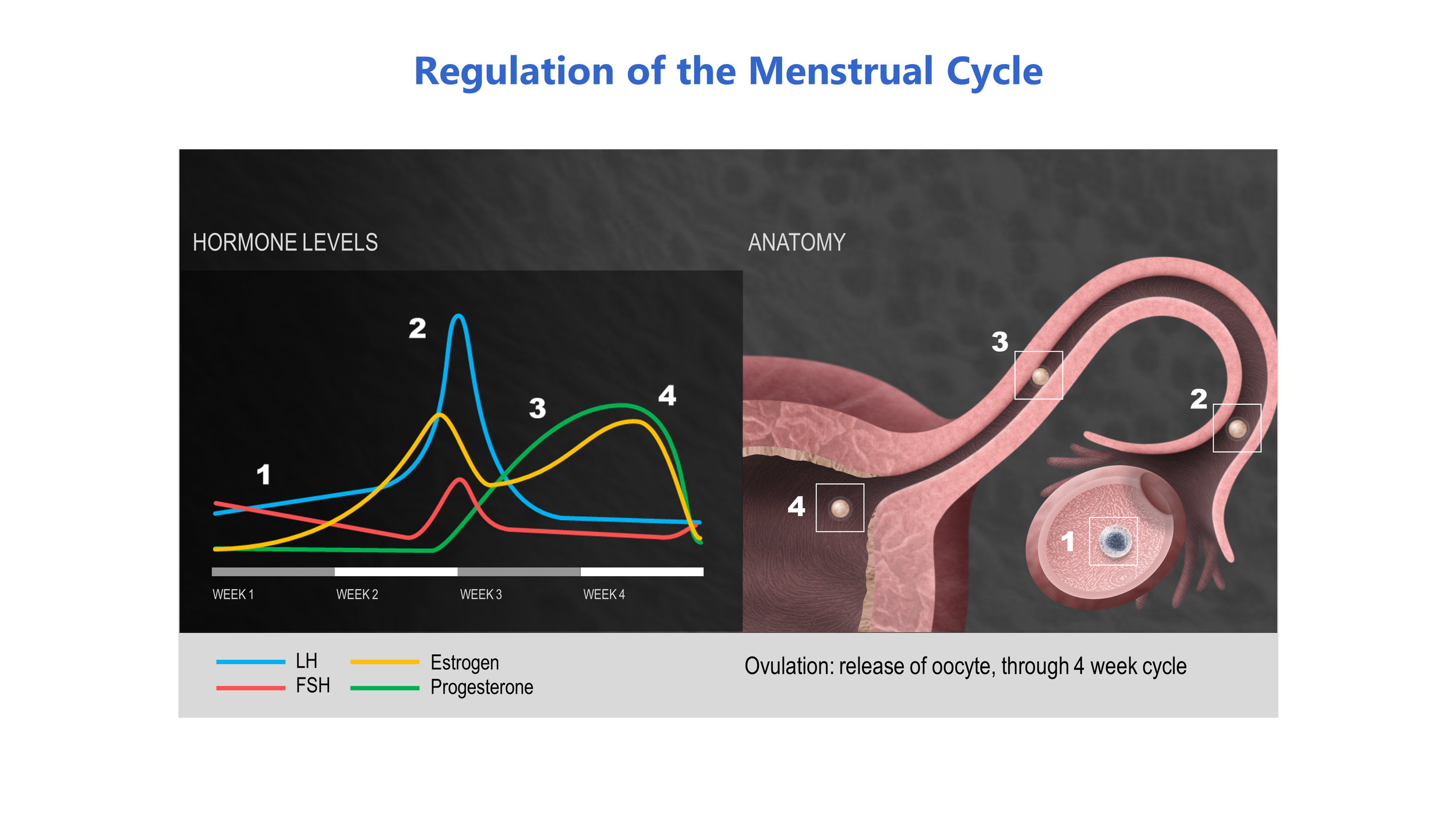

The 2D illustration / animation below was used to explain the phases of the menstrual cycle and how a patented oral contraceptive worked to alter the subject’s hormonal levels and prevent conception.